A note about substack: sometimes I spend days crafting these words. Most often I dash them off and use this place as a kind of online diary and sounding board. I am of the blog generation, and old habits write fast and die hard. Don’t judge me too much for the lack of polish.

A week ago I attended a conference at NYU as a guest of the International Beit Din, a rabbinical court that assists Jewish women whose husbands refuse to give them a Get. No, I am not Jewish. And yes, I was probably the only non-Jew in attendance that day (apart from the servers).

How did I end up there? Read on.

The Get

A Get, or religious divorce, is different to a secular divorce. It’s entirely possible to be divorced, say, under New York or California State Law, but to still be married under Jewish religious law (Halakah) because your husband refuses to give you a Get. I’m not going to go into this in any great length - for our purposes, it’s enough to know that because a Get is reliant upon a husband ‘giving’ his wife the divorce, it becomes another opportunity for men to wield coercive control and post separation abuse.

Last year I started shooting a documentary that followed a young mother called Helen. Helen filed for divorce from her husband after what most people would probably consider to be ‘minor’ domestic violence. That is, domestic violence which did not result in severe physical harm, and which took place over a relatively short period of time. Helen’s husband lied to her about their finances, became increasingly volatile and irrational following the birth of their first child, and eventually pushed her roughly enough in public that Helen was able to apply for a Domestic Violence Restraining Order. However, once Helen had removed her husband, Paris, from their apartment and started divorce proceedings, her life did not become easier, safer and calmer. Things got worse. He got worse. Her life became an endless round of court appearances and spurious legal filings and handing over her baby daughter for mandated custody visits and absolutely batshit crazy death threats.

Helen and I connected on an online group for mothers experiencing post-separation abuse and legal abuse. I started shooting this doc in February 2024.

As I make this documentary (make because it isn’t yet finished) I found myself not just looking for similarities between Paris and my ex, but desperately analyzing Helen’s every movement and comparing them to my own. Because Helen, unlike me, is now free. Three years after she left Paris, a year into the documentary, she has terminated his parental rights, and finally gained a divorce - and a Get. Paris is a fugitive in Israel with several outstanding warrants for felony stalking. Should he return to the US, he will be thrown in jail.

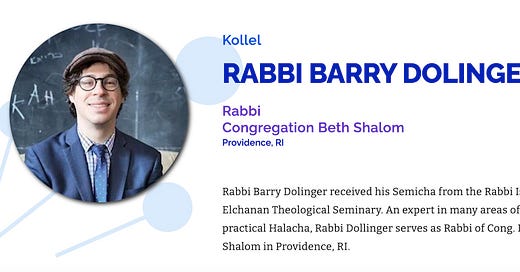

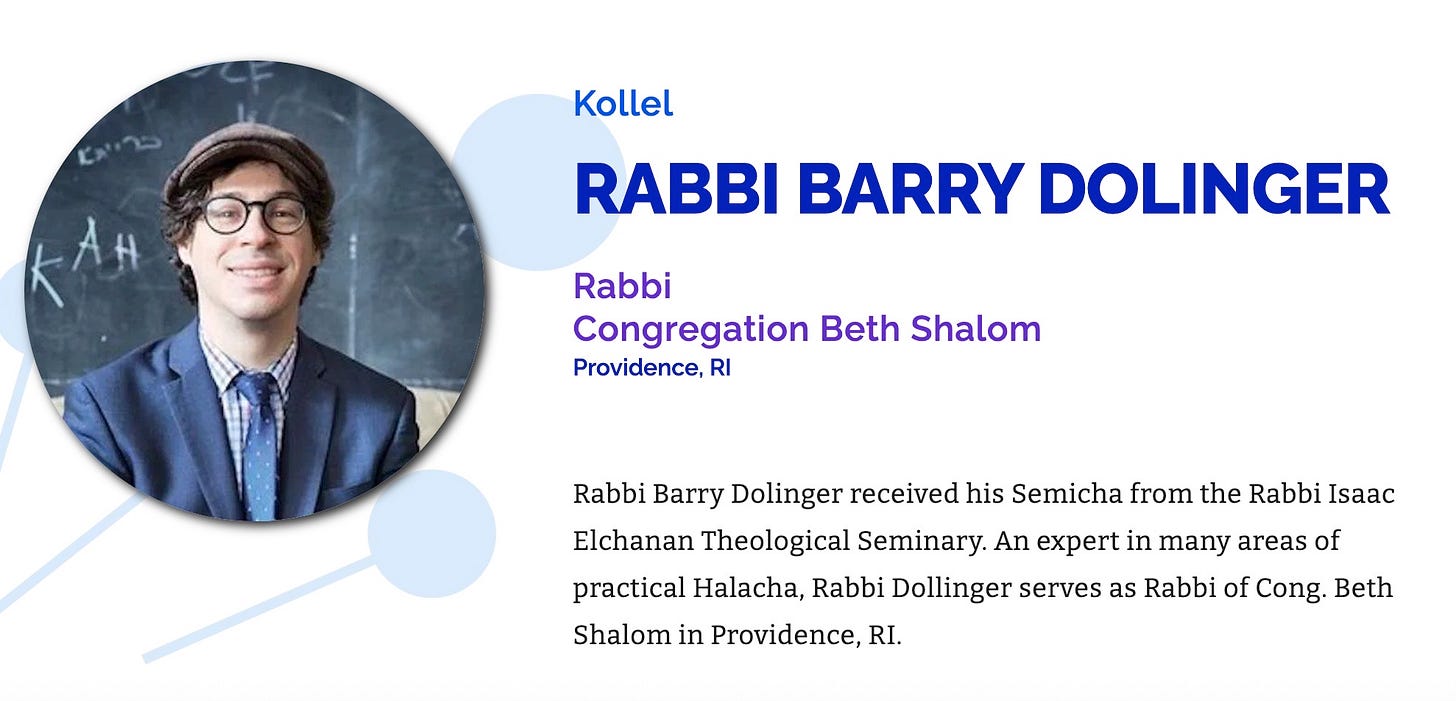

Early on in our filming, I was pulling on all nighter on the set of an Indie Film in Downtown LA. I’d been working 16 hour days, as we all do on set, and Helen emailed me and cc-ed Rabbi Barry Dolinger in, urging us to connect and film a segment together. I can’t remember his exact response, but it was short, warm, friendly and casual. I was confused why this young guy who looked like Harry Potter was concerned with Helen’s predicament. How was this dude a lawyer, and running a congregation, and head of a rabbinical court? So many questions which Helen seemed to take for granted. I noticed it wasn’t really surprising to her that Paris’ refusal to give her a Get would result in condemnation from her community. It wasn’t surprising to her that Barry was giving her his time, his organization was giving her a social worker, everyone was invested in keeping her and her daughter alive. Helen had also had incredible support from her school, CalTech, who provided her with a domestic violence counsellor from Peace Over Violence. This is extremely unusual. Believe me, I have tried to get help from USC. USC’s counsellors are not…. equipped.

Much of my last ten years has been about loss, and grief, and simply surviving. The absolute, incredible delight I have in my son is always, always tempered with the extremity of what I have had to give up to be his mother. That takes its toll after a month. After a year. After a decade. I wish I could say I am strong and powerful and educating the world and making a difference. Instead, I feel that I am grappling with depression, ongoing financial difficulties, and barely making a dent in people’s consciousness. I am alone. I feel that so acutely. People understand the death of a loved one. The hopeless longing and pain of infertility. The heartbreak of a relationship ending. We grieve for connections formed and broken, which dissolved, failed, or never materialized. We do not understand the stealthy malice of abuse you can’t measure in bruises and broken bones and calculated loss. We dismiss it. It can’t penetrate our consciousness as something that can cause as much destruction as these other palpable forms of human loss.

It’s hard to find peace in a life that has not been lived with agency. As Helen moves into the next phase of her life, my ex, nearly fifty, also moves into his, with a second child. I am not in any phase. I am here, just waiting for N to finally reach the point where he will be safe enough to leave me - and then, and then - what? I will be a decade away from retirement, but with no savings, and my career in tatters. I try not to think about it. I try to focus instead on telling Helen’s story, and I was invited to the conference specifically to screen a preview of the documentary for the attendees.

I find it hard to recall the good times with J. Recently, I’ve been trying to find these memories to share with N, so that he knows he wasn’t born in the same spiteful, anger that he was raised. I took him camping to Ojai this weekend, and I told him about the time J drove us out there in the rain for my birthday. About the campfire that refused to light, the waining, listless damp wood, the apple turnovers from Vons with a candle stuck in it for breakfast. I told N about J’s van which always broke down, so that I stopped planning anything when I knew he was going out to work, because I knew I would have to drive to rescue him when the van blew up again. I told N about running out of money, my Scientologist landlord throwing us out of the Weho cottage covered in roses with vines growing through the roof because he was sick of J, packing our belongings in a storage facility, driving to Ojai with nothing but two decrepit vehicles between us.

I told N about this time as we sat around a campfire in Ojai. I don’t think he believed me - the concept that his parents might once have been in love, have shown each other affection, have studiously avoided harming one another - is absurd to him. Preposterous. Ridiculous. I feel that way too, most of the time. I think about what I might have done differently to avoid the last ten years of hell. I think about the time my close friend in London took me to one side and said, after meeting J, “He’s very sensitive. Don’t hurt him.” I think about the chaos and panic that lurches in me from years of struggling with J, at the same time as trying to make rent, facing homelessness, having no safety net. I think about the mercurial speed at which I ricohet from one panicked, uncontrollable reaction into another: a stupid comment blurted, a misstep, a fall. “You’re sad-angry”, N said to me once. “Dad is just angry”.

Being around Helen, who knows my story, and has lived through her own, means dealing with a critic who makes no meal about the fact she finds me reactive, emotional and unstable - traits which I’ve always had, since childhood, but which have ballooned into daily monsters over the last decade of imprisonment. One of the worst things about living this life is that you go to court to tell them that you cannot cope because this situation has made your life intolerable. But then you are taken to court again and again, told that you are acting crazy, and unstable, and insane, because you are struggling to survive in a situation you clearly stated was not tolerable. We are reactive, emotional and unstable. We are living through hell, and these responses are appropriate. But we can’t admit to them. We have to be better. A woman undergoing any kind of domestic violence has to undertake a fucking marathon of epic proportions when she leaves the relationship. We need a holiday in Hawaii, love, support, community, help, healing. Instead we get court. More hell. No end in sight. At least when we were in a miserable marriage we had the illusion of a better life, the pretense that things might improve should we leave.

My favorite thing about the Beit Din Conference was that it wasn’t held by crying, shell-like women with haunted empty eyes. No offense, but I get that in the mirror every fucking day. It was held by - normal people. Just - regular members of society.

In the secular world, it’s unheard of that a room full of educated, smart, attractive, affluent and kind people might gather to acknowledge the possibility that the patriarchal systems they’ve built are causing more harm than good. In the secular world, we, the survivors, are doing the work, and the message is that everyone else really doesn’t have time to fuck around with this because mortgage rates are rising and fuck women and the end of the world is nigh. I don’t have parent friends here in the US. Not because they don’t believe me. But more because if they did believe me, they would have to admit their own moral and ethical complicity in normalizing the abuse that has now shaped me and N. It is so much easier for them to dismiss my situation as ‘two people who don’t get on’. It is enormously risky to hold an entire conference about the issue, invite doctors, lawyers, rabbis and activists from across the political and religious spectrum, and say simply, we failed women and mothers. We continue to fail them. Let’s be better.

The Get Refuser

From a feminist perspective, The Get is fascinating because of the way in which it is both a signifier of coercive control, and a means by which Jewish society can effectively recognize and reorganize to punish The Get Refuser. That is, a means by which The Get is a potential tool to challenge the patriarchy which formed it. Much of the pain I’ve suffered over the last ten years of coercive control comes from society’s refusal to acknowledge the coercive control my husband has wielded through the courts in the form of post-separation abuse. After a day with the Beit Din and its supporters, I started to realize that the kind of support Helen had from her community was instrumental to her freedom. I would go so far as to say, if Helen was not Jewish and did not have an Israeli passport, she would not be free today. Jewish society actively punishes a Get Refuser with financial sanctions which can run into thousands or more, and social sanctions which can result in an abusive husband being ostracized from his community. This is not to say Helen didn’t suffer. But there was an element where Paris’ behavior was instantly marked as problematic, wrong and abusive.

My issue, of course, was not that J denied me a divorce, but that he used the patriarchal power the courts gave him to claim custody of a child he was not mentally, physically or spiritually able to care for. He then used that power to curb my freedom, deny me access to community, home, culture, work and finances. This is the very definition of the Agunah - The Chained Woman. The relationship is over, the parties no longer live together - and yet the wife is still chained to the husband by his refusal to grant her freedom. His refusal to allow her to be anything other than his.

I kept blurting out - in my usual, uncontrolled, overly-emotional way - how grateful I was that the Beit Din was doing this work. I think they were surprised. They saw this as a Jewish problem. A halakah issue. They had forgotten, perhaps, that the same patriarchy rules us all.

I try to forget every single day. I really try.